I seem to have a badly leaking valve in my heart and need to undergo open-

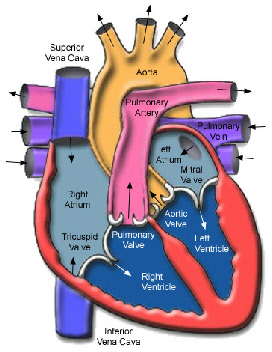

Technically I have Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP). From high school biology, you’ll remember that the left ventricle pumps blood rich in oxygen into the aorta and onward to the rest of the body through a vast system of arteries. The left atrium pulls blood from the lungs, freshly loaded with oxygen. The mitral valve keeps the blood flowing from the left atrium to the left ventricle. When the valve leaks blood back upstream, some of the work of the heart muscle is wasted, diminishing the flow down the arteries. A nice animation of the heart pumping can be viewed at the Links but a good illustration is below.

The heart does whatever is necessary to keep the body fed, so over time the ventricle

enlarges to compensate for the lost flow.  Meantime the upstream atrium is getting

more pressure than it should, causing it to also enlarge as a balloon would. Blood

can even back up into the lungs in severe cases. These enlargements are the ultimate

problem, because beyond some critical point the heart tissue is over-

Meantime the upstream atrium is getting

more pressure than it should, causing it to also enlarge as a balloon would. Blood

can even back up into the lungs in severe cases. These enlargements are the ultimate

problem, because beyond some critical point the heart tissue is over-

Symptoms of the leaky valve include shortness of breath and just plain being short

of energy, possibly fainting. But since the body compensates in so many ways, these

may not be immediately obvious. Except for the one fainting episode, I never have

experienced any of the symptoms. In fact most weekends I ride my bike 25-

The mitral valve gets its name from its resemblance to a bishop’s tall hat or miter,

and consists of two triangular leaflets. It is sometimes called the bicuspid valve.

The bad valve is considered to be "prolapsed" or floppy, which can be caused by the

two leaflets not meeting neatly, sometimes due to the old rheumatic fever, sometimes

you are born with it that way.

The bad valve is considered to be "prolapsed" or floppy, which can be caused by the

two leaflets not meeting neatly, sometimes due to the old rheumatic fever, sometimes

you are born with it that way.

Special cords (technically called "chordae" but sometimes thought of as "heart strings") are supposed to hold the valve halves in closed position, the way cords must hold a parachute in place to catch air. A muscle at the other end of the chordae quivers perfectly timed when the heart pumps to aid the process. If too many of the dozen or so chordae break or disease deforms the tissue, the valve is compromised.

The blood leaking severely back through the valve into the left atrium is regurgitating,

and makes a rushing sound much like the turbulence of a river going over rapids.

This noise is what is called a heart murmur, a pleasant-

Interestingly, around the mitral valve where that backwash occurs in the atrium is

a highly oxygen-

Fix Me Up, Doc

The corrective action for a severe MVP is pretty serious. Generally it is open-

Typically open-

Once inside, the doctors completely stop the heart (with great cold and some potassium-

The surgeon must go through the heart wall to get to the valve, trim up the tissue

so the two halves mate well, and reattach or reallocate broken chordae. This is the

art of surgery and requires tremendous knowledge, care, and skill. The final configuration

is tested to assure the valve isn’t still leaking before they stitch up the heart

wall, and a few minutes later they restart the heart to beat endlessly for the rest

of your life – no time for things to heal before they have to work full- I think it’s kind of funny that they lay down some pacemaker wires as they’re

closing you up – though I think these are removed a few days later – I imagine them

bringing in a car battery to jump-

I think it’s kind of funny that they lay down some pacemaker wires as they’re

closing you up – though I think these are removed a few days later – I imagine them

bringing in a car battery to jump-

Again, this stuff is pretty involved, although it is done every day by well-

There’s a smaller technique where they can maybe cut four ribs and get adequate access.

Then there is a minimally invasive approach where they go in with endoscopic utensils

and optics through very small holes between the ribs and do the work. The most exotic

approach is robotically-

Robotically-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS)

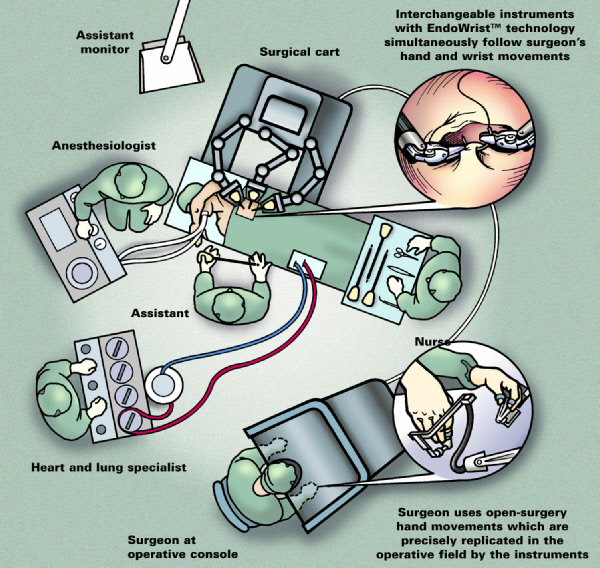

In this most advanced procedure, the surgeon sits at a console directing a robotic

machine while intently watching in 3-

While I expect to be able to take advantage of the most advanced techniques, should

the doctor need to back away and go with a more traditional approach, I figure Dr.

Chitwood has the experience to do that as well, evaluating all of the trade-

To provide a reference point, Dr. Chitwood had performed about 85 of these robotically-

Dr. Chitwood led the clinical trials for FDA approval of the da Vinci® machine made

by Intuitive Surgical for use in mitral valve repair. Dr. Chitwood has performed

more robotic-

Though he has demonstrated to a couple surgeons in Texas, so far nobody in the state

performs the minimally invasive, let alone the robot-

Even an endoscopic hand surgeon that fixed up my wife’s broken finger was glad to hear I was going to try a endoscopic approach because he struggles convincing other doctors and patients that the smaller instruments and cuts allow just as good a work to be done. The tried and true seems to dominate the thought processes in the medical world. Generally, that’s good, mind you. But I’m fairly confident that there is minimal additional risk and significant greater comfort in the minimally invasive technique.

Got a Map?

Before the MVP repair work, the surgeon needs a mapping of what he’s getting into. Everybody (every_body) is different, and you don’t want to get surprised if you can avoid it. Also, like with an automobile, if you’re going deep to repair something, if you can fix up a couple of other things while you’re in there, you might as well optimize your time. So a cardiac catheterization is requested before the MVP surgery.

I don’t know if it’s less squeamish than the more familiar kind of catheter, but

here they run a tiny plastic tube (the catheter) in an artery (and another in a vein)

and run it up to your heart.

This is an amazing process in itself. I can hardly fish

telephone wire up the wall from between the studs. And speaking of studs, they start

this catheter where the arteries are handy, down at the groin, so they’re pushing

3 feet of tube to reach the heart!

So why all the fishing around? With some sonic imaging type of machine watching, they can tell when they’ve got the catheter poised at the exit of the heart. Then they pump the slightest bit of iodine into the tube. The iodine is pretty dense so as it comes out the end of the tube they can see it disperse. They kindly refer to the iodine as "color" since they don’t like to use the word "dye" (die) when discussing patient’s hearts.

One thing they are doing is mapping the arteries that feed blood to they heart muscle itself. You don’t want to cut into one of these just because it isn’t where you think it should be. Also, these are the arteries that cause a heart attack if they can’t provide enough blood to the heart and the muscle starves out for oxygen. So they want to know that the arteries are clear. They can tap a little iodine into the arteries on the heart surface to see where they all are. They can also see if there are restrictions in these arteries to heart – the evil plaque build up due to all that chocolate, fried chicken, and butter. If you’ve got clogged arteries of the heart they had better prepare to clean those out while they’re in there. Mine were just fine, I’m happy to say, so pass me the Ben & Jerry’s.

They are also able to push the catheter a little farther, into my heart and show

that the iodine was backwashing into the left atrium through the mitral valve. Rats.

More confirmation. However, while in there they can also get highly precise measurements

of the pressure in the heart chambers – none of this cuff on the arm 12" away stuff

– we’re talking live, dead-

What Next?

So, I’m all set up now. I have great labs (blood tests show right-

North Carolina is farther to drive than I’d like, but airplanes get within 100 miles. The average stay at the hospital is a little over 3 days (!), which makes the insurance people happy, but the heck with them, I think it’ll make me happy. If you’re still OK a week later, then you can wander on home for final healing. Your wife has to tend to you and put up with you more than she’d like but she may see some benefit to having you around a few years longer too.

From what I can tell, there’s a good chance this is the only surgery like this that

I’ll ever need. While, frankly, there isn’t enough data to go on for the robot-

Anesthesia is always risky, but you’re hopefully cutting down dramatically on exposure to the ugly environment with the smaller cuts, and less trauma to muscle, tissue and bones. Less than 20% of the time do patients require transfusion to top up for blood loss. I’m as healthy as they get so it’s far better to do this now than when I’m 10 years older. I’ll have to spend my 49th birthday in the Intensive Care Unit, but if you were a betting mathematician, you’d know that 7 x 7 = 49 so I’ll have a multitude of luck going my way.

But you have to remember, all these guys can do is put me back where I was. They may fix my heart back to being the fine machine it once was. And you know how kind, generous, and loving I am. They can’t improve that mythical aspect of the heart, so I’m not likely to come out like Mother Teresa. So don’t get your hopes too high.

scroll down to the jump table to go to the desired section

The surgeon has better dexterity than large fingers normally could manage (though

I think these guys thread needles with garden twine in their sleep) giving him much

more precise control of his work (her too). I liken the robotic-

Robotic minimally-

Other advantages of using the computer-

By pure odd coincidence, earlier this year I ran into a design engineer from the company (Intuitive Surgical) that makes the robotic surgery machine at an electronics conference and I talked his ear off to get comfortable with the technology.

What’s with the Beard?

And how did all of this come about? One weekend at the end of March I was feeling

poorly so I took a nap, ate lunch, and took a shower. S omehow I fell and cut my chin.

I made Jan take me to get stitches (after all, this was my pretty face we’re talking

about). At the emergency room they weren’t at all concerned about my split chin,

but focused on why I fell.

omehow I fell and cut my chin.

I made Jan take me to get stitches (after all, this was my pretty face we’re talking

about). At the emergency room they weren’t at all concerned about my split chin,

but focused on why I fell.

My pulse and blood pressure were right on, but they didn’t like the murmur, so when I couldn’t come up with a reason for falling, they figured I had fainted, if ever so briefly (the pain in my chin quickly brought me around). They hooked me up for an EKG and sent me to a cardiologist. They did finally stitch the cut in my chin closed.

So now with these stitches in my chin, my shaving had to take a back seat. A couple weeks into this, Jan actually looked at me (after 20 years of marriage, I wonder if she ever still looks at me) and said "hey, that beard looks kind of neat!" and she had that special look in her eye. So, like a schoolboy hoping to get a little extra attention from a girl, that was all the encouragement I needed. Even though Jan had never before liked facial hair on me and it’s a real nuisance to trim up, I thought I’d keep the Van Dyke. I guess the beard became the badge of my defect. Since my "getting lucky" didn’t live up to its promise, I decided to lose the beard once I got myself fixed – that is, got my heart fixed.

Draw me a Picture

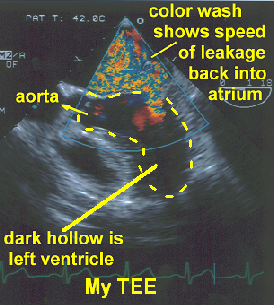

The cardiologist asked for a sonogram, just like they do when you’re pregnant (you,

not me). Watching my heart on this, they figured I had this leaky valve. It’s pretty

cool to see your own heart beat in real- Apparently your heart is right next to your esophagus and they can get a clear picture

of the heart in action without all the dense bones and stuff in the way.

You end up with a Doppler picture that shows with color how much flow you have in

all the chambers. It is kind of like the weather radar (upper image, with lots of

green) but instead of density of moisture, the color shows flow. In my case (lower

image, dark kidney shape is the left ventricle) the colors highlight the backwash

into the atrium when the heavy pumping is going on in the ventricle, and that’s what’s

wrong.  The TEE is the definitive tool for confirming the faulty valve. I suppose

the proximity of the heart to the esophagus explains your feeling "heart-

The TEE is the definitive tool for confirming the faulty valve. I suppose

the proximity of the heart to the esophagus explains your feeling "heart-

There are three options for a bad valve. The best is repairing the original valve.

Fix what you have. This is part of your body and while not perfect, it is native

tissue. Should the original valve not be repairable, then a substitute made of pig

or cow tissue can be used. Since that would be non-

The other choice is to use a mechanical valve, something like a ball in a cage and

other designs (probably a million of these have been implanted over the years). Blood

thinners (anticoagulants – coumadin) are needed to keep man-

Decisions. Size Matter s

s

I was quickly fascinated by the minimally-

Numerous discussions of minimally-

Theatre Layout Illustration from Intuitive Surgical's Web site

(www.intuitivesurgical.com/news_room/downloads.html)

©Intuitive Surgical 2003

|

0. Prologue |

1. About MVP |

2. In Hospital |

4. Show Me |

5. Conclusions |

6. Follow- |

|

0. Prologue |

1. About MVP |

2. In Hospital |

4. Show Me |

5. Conclusions |

6. Follow- |

Copyright ©2003-